Now that it appears Congress will pass the bailout plan the next logical question is “what’s next?” I don’t know the answer, but I have my concerns.

This plan may well deal with the current stresses in the financial markets. If so, we can all stop panicking that the world as we know it will come to an abrupt end and get back to the real economy. But, as one commentator just said on CNBC, this may put the fire out but the furniture is still burned. The problem is that the real economy isn’t doing too well. Unemployment is up, spending is down, people are concerned, so where are we headed from here? First, lets see what the current plan hopes to accomplish.

Here is the problem. If a bank has lots of bad assets on its balance sheet, it can’t sell them because if it does it takes a loss on the sale. That loss reduces the bank’s capital, and without adequate capital a bank cannot make loans. On the other hand, if the bank just holds on to the bad assets, it can’t raise new cash to make loans because no one wants to lend it money without knowing how bad the bank’s balance sheet actually is. So as long as these bad assets are being held by the banks lending activity slows or, in the worst case, stops all together. If this gets really out of hand and these bad assets start showing up in other places (like money market mutual funds) then investors start taking their money out of all the places they invest and all lending could stop. That would be the modern day equivalent of a run-on-the-banks. No loans, no economic activity and we fall into a very bad economic shutdown. The only difference between this kind of bank run and the classic depression era run is that the taxpayers stand behind the deposits in commercial banks today through the FDIC and Treasury so we collectively insure our deposits. This prevents a run on commercial banks. We don’t, however, insure the funding sources for all of the other financial institutions in our financial system. Money market mutual funds, insurance companies, investment banks, hedge funds, and private equity raise funds that are not insured against loss. When these bad assets start showing up in those places the sources funding them run. This is why the federal government announced an insurance plan for money market mutual funds last week, and is also why we have witnessed the demise of the independent investment banks. The investors in these banks have stopped funding them – a run on the investment banks. So, although commercial bank deposits that most Americans have in their bank are insured, there is an entire system of finance that doesn’t have this protection and is prone to a classic run. That run is in progress. The current plan hopes to remove bad assets from balance sheets of financial institutions so that lending will return to the economy and investors will stop running. It is intended to “unplug” the flow of money throughout the system by taking away the source of the clog – these bad assets. But even if it works, where do we end up?

A while back I posted an article that explained how the level of household debt to personal income has grown too high and until consumers pay down their debts to a level they can afford the economy will not do well. This is parallel to what is happening in the housing market. Until prices return to a level that makes purchasing a home affordable for the average homeowner prices will decline. As far as overall household debt is concerned, until it returns to a level supportable by personal incomes debt must be reduced. How do we reduce debt? We save rather than spend. Saving more and spending less means less economic activity, and that means a possible recession. So how does the rescue plan deal with this issue? I don’t think it does because it doesn’t deal with the bottom up issue that consumers are in too much debt. How much debt are US consumers in? Total household debt is about $14 trillion, or approximately 145% of 2007 annual disposable personal income. What was this ratio the last time we went into a banking crisis in, say, 1991? It was approximately 85%. That leads us to a thought experiment. What would it take to get us back to the levels of debt to income that we had during the last crisis? If we assume disposable personal income will grow by 2% for this year, then personal income for 2008 should be approximately $9.8 trillion dollars. At 85%, household debt would be approximately $8.4 trillion. Since actual household debt is currently in the $14 trillion range, we need to de-leverage about $5.6 trillion to get back to the 85% ratio we had in 1991. In a $14 trillion economy that represents about 40% of one year’s GDP. In fact, it’s even worse than that because if we stop borrowing in order to save then we also lose the GDP funded by debt (another $880 billion). Comparing other developed countries that have seen similar increases in household debt to disposable personal income, Japan stands out as it went over 120% in – you guessed it, 1991 (see page 47). This was the start of the “lost decade” for Japan.

I don’t expect we would make up all 40% of our adjustment back to 1991 in a short period of time, nor am I convinced that we will ever actually get there without a major new boom in real economic activity (such as discoveries relating to new energy technologies) or a major bust where debt gets written down in mass quantities. The situation does, however, point us to what we can expect next. Expect a rather protracted recession and/or more government interventions into the economy before this is over. I expect the next intervention will be of the bottom up sort, and eventually if the Federal Government owns enough mortgages I can see debt forgiveness of underlying mortgages owned by taxpayers.

Debt numbers: here

Personal Income numbers: here.

Thursday, September 25, 2008

What the Plan Does (and does not)

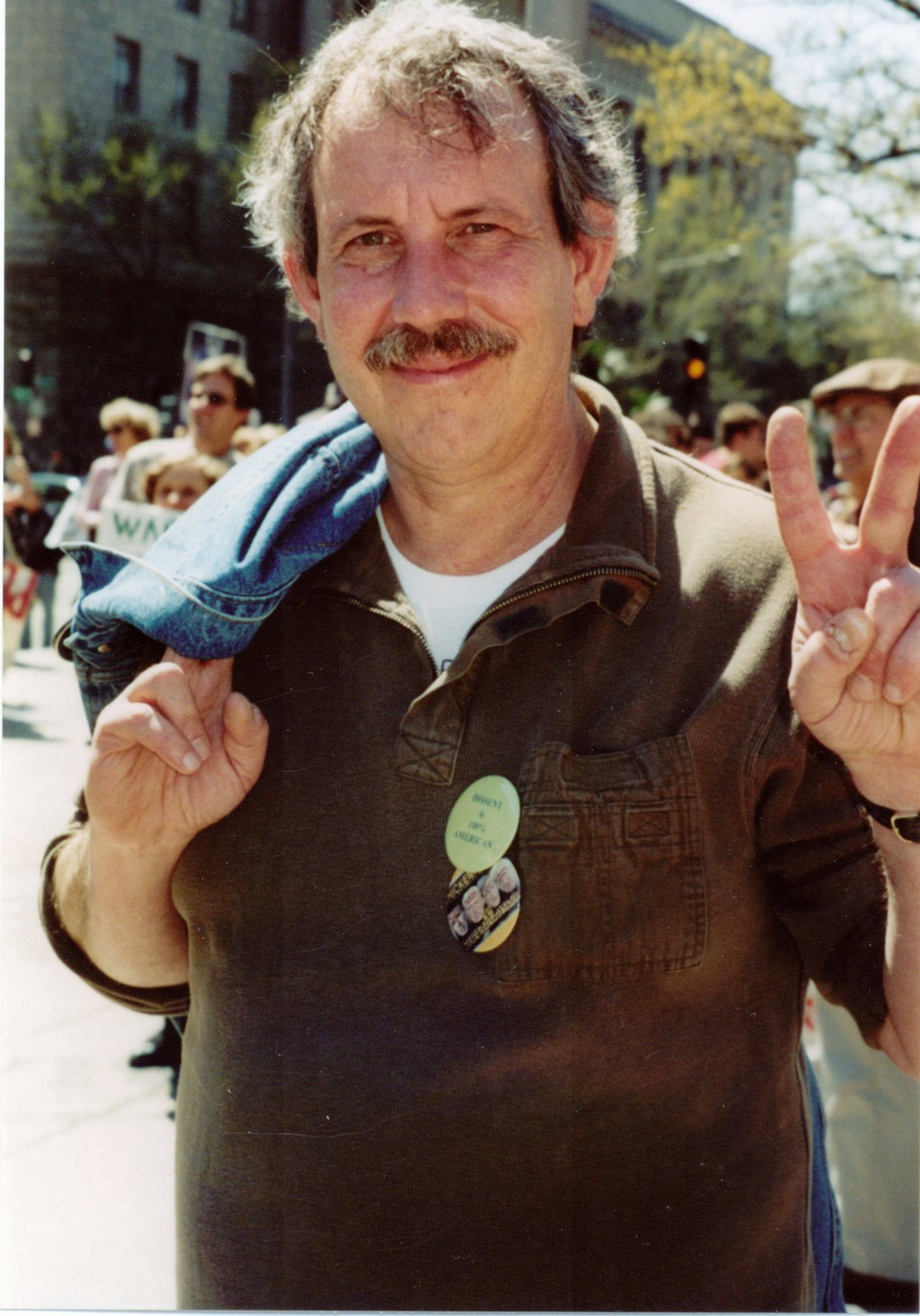

Posted by

Palermo's Blog

at

3:39 PM

![]()

Labels: bailout, debt, depression, economy, intervention, personal income, recession, taxpayer

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

1 comment:

I though the entire point of this $700 billion plan (and I might be looking through rose colored glasses) was to help the home owner and banks would be favorable impacted by but by proxy (unavoidable proxy). I thought the 700 billion was going to be used to buy these toxic assets than call homeowners who have defaulted or who are in danger of defaulting and offer them an affordable mortgage (student loan or credit card payment plan if those are being bought too, i dont think we really know) say 30 years fixed at 3%. I thought this bailout plan was a bailout of the overleveraged american public and a plan to keep people in their homes. Unfortunately it helps out a lot of people and banks that dont deserved to be "bailed out" but i think that is an unavoidable consequence at this point.

So i think this plan does help deleverage americans. And i think it will simulate the economy, if homeowner were previously paying $5,000 for their mortgage and this plan causes their payment to go down to $3,000 it frees up disposable income that will hopefully be pumped back into the economy and if reduces their debt.

Possible the government and we as tax payers will benefit from owning these assets. Previously none of these mortgages would have been paid, now they will get paid earn some modest interest (3% maybe).

Post a Comment